Edgar Rice Burroughs' classic tale is brought to life through the beautiful imaginings of Burne Hogarth. His psychedelic vision of jungle ferns and plant life is visually arresting. The following images are taken from the book 'Tarzan Of The Apes' published in 1972 by Watson-Guptill Publications, New York.

Tuesday 16 November 2010

Friday 12 November 2010

R. Crumb's Drawings of Buildings

Being a fan of R Crumbs' work I wanted to share these drawings of buildings from the book "The Sweeter Side of R. Crumb". There isn't any text to accompany the images other than the titles, but I know that he lives in the south of France, and so I presume that these are buildings that are near to his home. Anyway, I wanted to post these today because of, quite simply, how beautifully rendered they are. Although Crumb's work is pretty varied, it's nice to see some stuff that isn't just women's legs etc...

(be sure to click on the images to see bigger versions as the detail is amazing on these!)

Tuesday 9 November 2010

Drawing Now Exhibition

In December 2002 I went on a university trip to New York. Whilst there I visited the Museum of Modern Art which was running and exhibition called 'Drawing Now: Eight Propositions'. I was highly impressed with some of the work on show and bought a book as to not forget what I had seen. The work I saw that day made a great impression on me in many ways and below are a few examples of some of my favourites.

David Thorpe

We Are Majestic in the

Wilderness, 1999

Paper collage,

70 7/8 x 57 1/16" (180 x 145 cm)

David Thorpe

Evolution Now, 2000 - 2001

Paper Collage,

43¼ x 27½" (110 x 170 cm)

David Thorpe

Pilgrims, 1999

Paper collage,

46¼ x 68" (117.5 x 173cm)

Paul Noble

Nobspital, 1997-98

Pencil on paper,

8' 2½ x 59" (250 x 150 cm)

Julie Mehretu

Untitled, 2000

Ink, coloured pencil, and

cut paper on Mylar,

18 x 24" (45.7 x 61 cm)

Yoshitomo Nara

U-ki-yo-e, 1999

Oil on book pages,

one of sixteen parts,

16 5/8 x 13" (42.1 x 33 cm)

Light Model: Northwest View (2), 2002

Liquid acrylic and pencil on paper,

22½ x 30" (57.2 x 76.2 cm)

Matthew Ritchie

Everyone Belongs to

Everyone Else, 2000 - 2001

Ink and graphite on plastic

sheet, one from suite of

seven drawings, each 22 x 65"

(55.9 x 165.1 cm)

Images are taken from the book 'Drawing Now: Eight Propositions', 2002. The exhibition took place from October 17, 2002 to January 6, 2003 and was organized by Laura Hoptman.

Saturday 6 November 2010

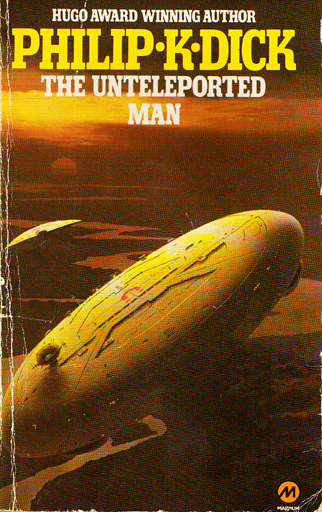

Philip K Dick on Science Fiction

I am a huge Philip K Dick fan, I would go as far as to say he is my favourite author of all time. I would also say that I am a big science fiction fan in general, but for me Philip K Dick goes far beyond the genre; his novels explore metaphysical and existentialist themes, as well as sociological and political ideas. Dick actually described himself as a 'fictionalizing philosopher'.

In the preface of "Beyond Lies The Wub" (volume 1 of his collected short stories), there is a fantastic piece of writing from 1981 in which Philip K Dick explains his definition and ideas on what is science fiction and what makes good science fiction;

"I will define science fiction, first, by saying what it is not. It cannot be defined as "a story (or novel or play) set in the future," since there exists such a thing as space adventure, which is set in the future but is not sf: it is just that: adventures, fights and wars in the future in space involving super-advanced technology. Why, then, is it not science fiction? It would seem to be, and Doris Lessing (e.g.) supposes that it is. However, space adventure lacks the distinct new idea that is the essential ingredient. Also, there can be science fiction set in the present: the alternative world story or novel. So if we seperate sf from the future and also from ultra-advanced technology, what then do we have that can be called sf?

We have a fictitious world; that is the first step: it is a society that does not in fact exist, but is predicated on our known society; that is, our known society acts as a jumping-off point for it; the society advances out of our own in some way, perhaps orthogonally, as with the alternative world story or novel. It is our world dislocated by some kind of mental effort on the part of the author, our world transformed into that which is not or not yet. This world must differ from the given in at least one way, and this one way must be sufficient to give rise to events that could not occur in our society - or in any known society present or past. There must be a coherent idea involved in this dislocation; that is, the dislocation must be a conceptual one, not merely a trivial or bizarre one - this is the essence of science fiction, the conceptual dislocation within the society so that as a result new society is generated in the author's mind, transferred to paper, and from paper it occurs as a convulsive shock in the reader's mind, the shock of dysrecognition. He knows that it is not his actual world that he is reading about.

Now to separate science fiction from fantasy. This is impossible to do, and a moment's thought will show why. Take psionics; take mutants such as we find in Ted Sturgeon's wonderful 'More Than Human'. If the reader believes that such mutants could exist, then he will view Sturgeon's novel as science fiction. If, however, he beleives that such mutants are, like wizards and dragons, not possible, nor will ever be possible, then he is reading a fantasy novel. Fantasy involves that which genral opinion regards as impossible; science fiction involves that which general opinion regards as possible under the right circumstances. This is in essence a judgement-call, since what is possible and what is not possible is not objectively known but is, rather, a subjective belief on the part of the author and of the reader.

Now to define good science fiction. The conceptual dislocation - the new idea, in other words - must be truly new (or a new variation on an old one) and it nust be intellectually stimulating to the reader; it must invade his mind and wake it up to the possibility of something he had not up to then thought of. Thus "good science fiction" is a value term, not an objective thing, and yet, I think, there really is such a thing, objectively, as good science fiction.

I think Dr. Willis McNelly at the California State University at Fullerton put it best when he said that the true protagonist of an sf story or novel is an idea and not a person. If it is good sf the idea is new, it is stimulating, and, probably most important of all, it sets off a chain-reaction of ramification-ideas in the mind of the reader, it so-to-speak unlocks the reader's mind so that the mind, like the author's, begins to create. This sf is creative and it inspires creativity, which mainstream sf by-and-large does not do. We who read sf (I am speaking as a reader now, not a writer) read it because we love to experience this chain-reaction of ideas being set off in our minds by something we read, something with a new idea in it; hence the very best science fiction ultimately winds up being a collaboration between author and reader, in which both create - and enjoy doing it: joy is the essential and final ingredient in science fiction, the joy of discovery of newness.

(in a letter)

May 14, 1981"

Below are a few scans of some novels that were published during the 1970's:

Art by: Bruce Pennington

Art by: Chris Moore

Art by: Unknown

Art by: Chris Moore

Thursday 4 November 2010

Esteban Maroto

Today I present the work of Esteban Maroto. Born in Madrid in 1942, Esteban Maroto started out his career in the early 1960's working under the guidance of Manuel López. His style was established in a series called 'Cinco Por Infinito' (published in English by Continuity Comics as 'Zero Patrol'), in 1967. This was followed by 'La Tumba de los Dioses', his 'Alma de Dragon' in Trinca magazine was also successful.

As things progressed into the 1970's, he started to produce, in my opinion, some of his best work. One of my favourite and most inspirational books I own is the 'Dracula Annual', published by the 'New English Library' (NEL) in 1972. The strips originally featured in the comic 'Dracula', and were later compiled into this hardback book which featured;

'Wolff' - by Esteban Maroto

'Sir Leo' - by Jose Bea

'Agar Agar' - by Alberto Solsona

and 'A Horror Strip' by Enric Sio

I've seen many examples of artists working outside the limitations of panels before, but Esteban Maroto certainly has his own way of acheiving this. Instead of telling the story through a series of panels he'll often tell it through the arrangement and composition of drawings; the combining and layering of images. This helps to give the image movement as the eye naturally swings around the page. When drawing these comics, Maroto was more than aware of what it was that his audience wanted - strong overtones of sex and raw barbarian fantasy; and he always delivered.

Although his stories were usually short, he made up for this, I feel, in the quality of his rendering, a truely immaculate and elegant style. His ability to capture the female form is, at times, flawless. One area of Maroto's work that has been criticized is his writing. Many people claimed that he could never write a good fantasy tale, I however, don't see this as an issue. For me, there are different reasons for liking different comics, for example; some comics are to be enjoyed for their ability to tell a good story and may not always be drawn in a style that is particularily appealing. And then there are some that are to be enjoyed for their aesthetic appeal, and then there are some that meet both criteria. In my opinion, the majority of the stories in the Dracula Annual are to be appreciated for their aesthetic value primarily.

Also during the 1970's and 80's, Maroto drew comics for Creepy, Vampirella and Eerie. During this time he also worked for Marvel in black-and-white on 'Red Sonja' and 'Conan'.

Below, there are a few examples of his work from the Dracula Annual' and also the full strip from my favourite of the collection, entitled 'The Viyi'. I have also included some examples of his later work on 'Atlantis Chronicles' from 1990, and (the superior) 'Amethyst' from 1987 / 88 (both published by DC). Enjoy!

The Viyi

Amethyst

Atlantis Chronicles

Tuesday 2 November 2010

Epic Illustrated #3 - P Craig Russell

Another artist, fast becoming one of my favourites, is P. Craig Russell. The following strip appears in 'Epic Illiustrated' (3rd issue, Fall 1980, Marvel); the title of the strip is 'A Tale of Elric of Melniboné - The Dreaming City Part One'.

I will be presenting more work by P Craig Russell in the near future, this is just a taster, enjoy!

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)